The “Nonsense” Botanical Illustrations of Victorian Artist-Poet Edward Lear (1871–77)

Because the Victorian period, Edward Lear’s “The Owl and the Pussy-Cat” has been, for generation upon generation within the English-speaking world, the sort of poem that one simply is aware of, whether or not one remembers actually having learn it or not. As with most such works that seep so permanently into the culture, it doesn’t fairly repredespatched its creator in full. Although kind of of a chunk with his celebrated “nonsense” verse (which I personally learn in little onehood, greater than a century after its initial publication), it hints solely imprecisely at his intense artistic interactment with the natural world, via the observation and stayly portrayal of which he made his identify as an illustrator.

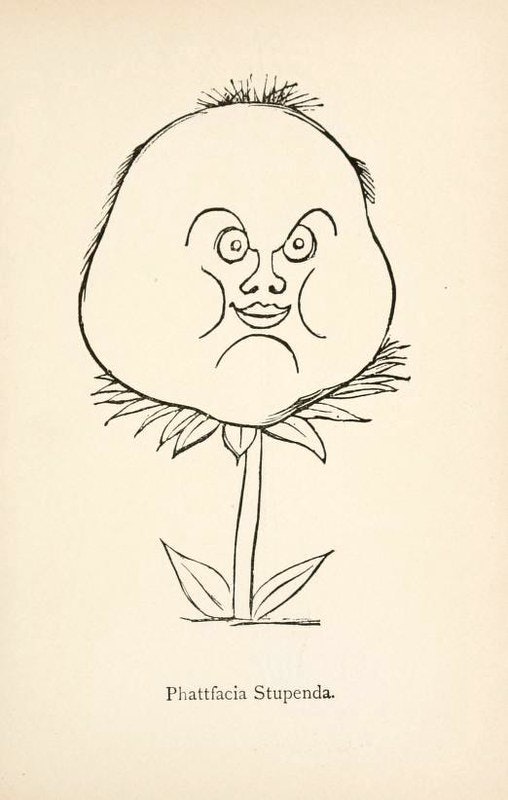

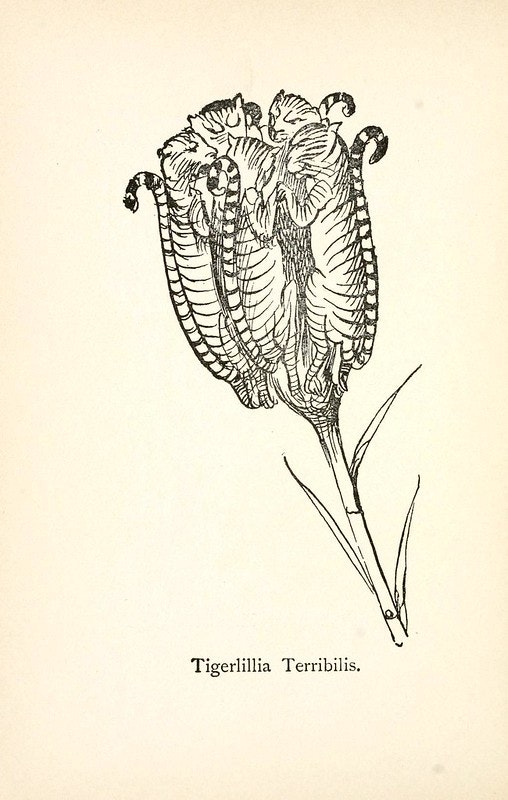

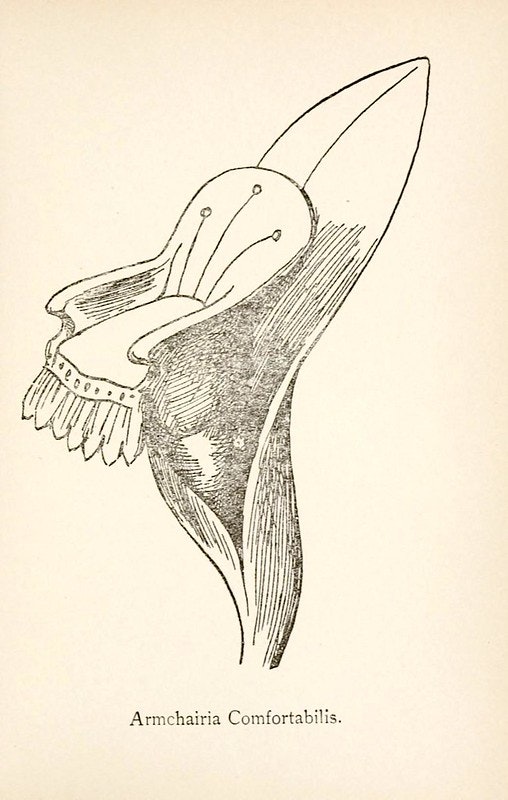

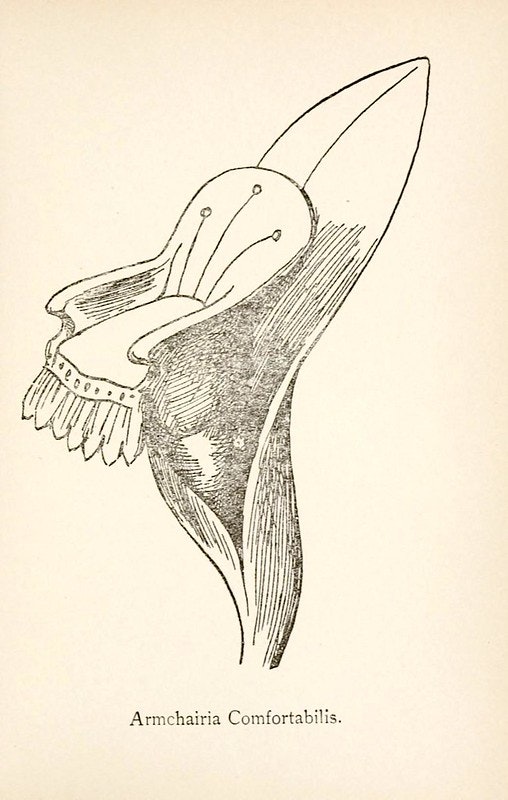

“Lear was an attentive and knowledgeable learner of Darwin; he labored with John Gould, the natural-history entrepreneur who had actually picked aside the varieties of finch that Darwin had introduced again from the Galápagos Islands,” writes the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik, noting that his work evidences a Linnaean obsession “with the power of naming, with sticking a tag on a factor which provides it a spot at, and on, the desk.” Lear gave Latin names to at the very least two actual species of parrots, however he additionally fabricated such chimeras as Phattfacia Stupenda, Armchairia Comfortabilis, Tigerlilia Terribilis, examinationples of which he additionally illustrates in his Nonsense Botany collection of the eighteen-seventies.

Lear’s “penchant for the natural world,” says The Dilettante, formed his “knack for inventing ridiculous landscapes and anthropomorphizing all sort of creatures and objects. The result’s a surreal Learean world of Scroobious Pips, Quangle Wangles, and Nice Gromboolian Plains.” His “fanciful re-sculpting of the physical world is brilliantly exemplified” in his Nonsense Botany, with its “sketches and entertaining captions learn as a taxonomy of incongruous plant-creatures.” Whether or not on the Public Area Overview or Venture Gutenberg, you’ll be able to gaze upon all of them and experience not simply gentle amusement, but additionally a sort of astonishment at Lear’s peculiar talent: he doesn’t “discover the amazing within the ordinary,” as Gopnik places it; “he finds the ordinary within the amazing.”

through Public Area Overview

Related content:

Based mostly in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His tasks embrace the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the ebook The Statemuch less Metropolis: a Stroll via Twenty first-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Faceebook.